Fri 16 Nov 2012

Construction Lead Paint- follow EPA or OSHA

Posted by admin under Air Monitoring, Biological Monitoring, Dust, EPA, Federal OSHA, HEPA, Lead, OSHA, Personal Protective Equip (PPE), Respirators, Safety Programs, Training, Uncategorized

1 Comment

You must follow both. (I’ve mentioned this before)

OSHA’s rules are very detailed and apply to any amount of lead in paint (even less than 0.5%) if you are disturbing it. The only time OSHA rules do not apply is:

- if you are working as a sole-proprietor (no employees), or

- if you are in some other country.

EPA’s rules are just a start. They apply to any residential facility where there are kids under the age of 6. OSHA’s rules are much more comprehensive and protective. (in some instances, overkill)

To EPA’s credit, they have done a great job of marketing and letting contractors know they insist on compliance. OSHA, on the other hand, only inspects 2% of businesses/year and does virtually no marketing. The chances of OSHA showing up on any given jobsite, is nearly 0%.

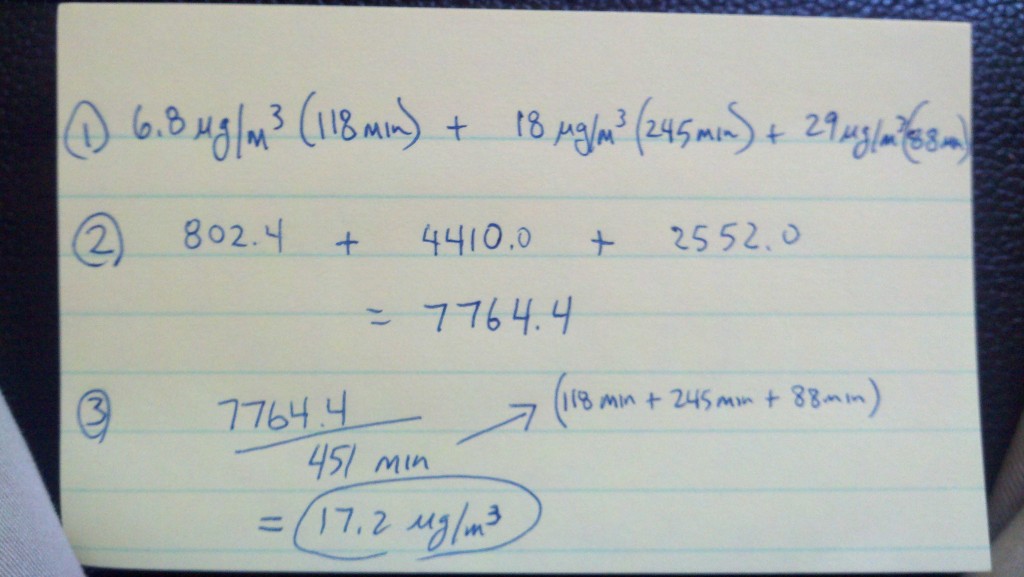

OSHA’s rules are very complete and comprehensive. You WILL need air monitoring, blood monitoring, PPE, change areas, water/sanitation, and training. The worst thing you can do is NOT follow the OSHA rules, find overexposures, and then try to “make up” for it. From my experience this scenario is a bad place to be, and happens all the time.