Wed 27 Nov 2013

Top 10 Hazards of drywall

Posted by admin under Asbestos, Building Survey, Dermal, Drywall, Dust, Exposure, Fall Protection, Gloves, hearing protection, Ladder, Ladders, Lead, Leaded Sheetrock, Management, Noise, occupational hygiene, OSHA, Powder Actuated Tool, Respirators, safety, Silica, Uncategorized

Comments Off on Top 10 Hazards of drywall

I titled this post, “hazards of drywall”, but it encompassing most of the common hazards of plaster, mud, gypsum, wall-hangers, tapers, and acoustic employees.

-

Corrosive drywall.

I have not dealt with this subject on a personal level. However, AIHA has a new guidance document titled, “Assessment and Remediation of Corrosive Drywall: An AIHA Guidance Document“, which is a clarification of an earlier white paper document from 2000, titled, “Corrosive Drywall“. The danger is from a specific type of drywall which was imported from China. After installation it is known to emit sulfide vapors, which corrode copper (electrical wires), and can give off a sulfur smell (HT to JeffH in Ohio).

-

Asbestos in mud/plaster.

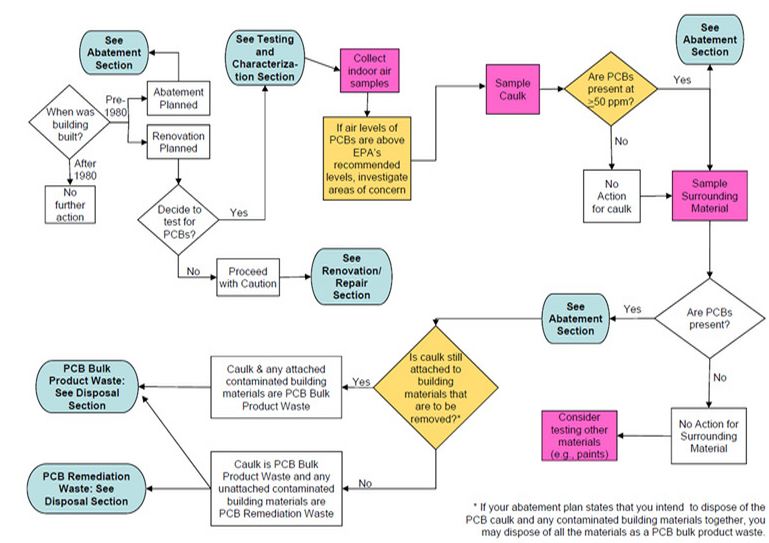

Be aware, some older buildings (pre 1980s) may have asbestos in the mud compound or plaster (not as common). This will be a concern if you are performing demo on these walls. Info here.

-

Silica (dust) in joint (mud) compound.

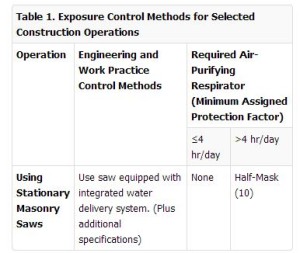

Some types of silica I have found to have silica. This can be an issue when sanding. AND, if you install drywall like me…you do a lot of sanding. More information from an earlier post can be found here. NIOSH has some suggestions too.

- Leaded sheetrock. If you are installing (or demo) leaded sheetrock, you NEED to protect yourself. Airborne levels of lead can approach the exposure limits, even during installation. More info here.

- Lead in paint. If you’re tying into existing plaster/drywall and there’s paint, you need to know if there’s lead in it. Sanding on the paint is a good way to be exposed. More info here.

- Ergonomics. Hanging the wallboard takes a toll on your body after 20 years (or less). Not to mention sanding. Washington OSHA (L&I) has a good demo.

- Noise. Cutting steel studs, powder actuated tools (there’s lead exposure too, you know).

- Skin hazards. Cutting, but also dermatitis from prolonged exposure to dust.

- Eye hazards. Dust, carpentry, etc. Working overhead is an easy way to get falling items in your eyes.

- Falls. Last on my list, but certainly not the least. Scaffolding, working from ladders, and using stilts, to name a few.